Dozens of reporters, videographers and photographers thronged around the yellow tape surrounding the block containing the Ghost Ship warehouse the morning after the tragic fire that killed 36 people in the center of Fruitvale. As the hour approached noon, a group of thousands of Latino Catholics began their scheduled annual procession for the Virgen de Guadalupe from St. Elizabeth’s Church, one of the largest Latino Catholic parishes in the Bay Area, located just three short blocks away from the site of the fire. Their normal route for the yearly march from the church to the Diocese headquarters in downtown Oakland is down the length of International Boulevard until it rebounds off of Lake Merritt.

Dozens of reporters, videographers and photographers thronged around the yellow tape surrounding the block containing the Ghost Ship warehouse the morning after the tragic fire that killed 36 people in the center of Fruitvale. As the hour approached noon, a group of thousands of Latino Catholics began their scheduled annual procession for the Virgen de Guadalupe from St. Elizabeth’s Church, one of the largest Latino Catholic parishes in the Bay Area, located just three short blocks away from the site of the fire. Their normal route for the yearly march from the church to the Diocese headquarters in downtown Oakland is down the length of International Boulevard until it rebounds off of Lake Merritt.

But on that morning, the procession was forced to reroute to 12th street, as the city of Oakland had shut down International Blvd for the three square blocks from Fruitvale to Derby St. The procession seemed never-ending, and the street was teeming with people. They were all Latinos, as the Fruitvale and San Antonio districts have for generations been an eclectic mix of Central American, Mexican and African-American communities. Sunday is a big community day around the church, where during any scheduled service, the crowd is standing room only, with even the vestibules full of parishioners.

That Sunday, the day after the fire, wave after wave of the procession curved around the yellow hazard tape, and onto 12th Street, but journalists and photographers alike shrugged at the spectacle. Nothing about the procession: its existence, its character, its juxtaposition with the disaster nor, most importantly, the fact that thousands of community members were available for comment, attracted the attention of the media.

The Caminata de la Virgen de Guadalupe, an annual event of St. Elizabeth’s Church, snakes past the police cordon of the Ghost Ship fire on Sunday, December 3, 2016.

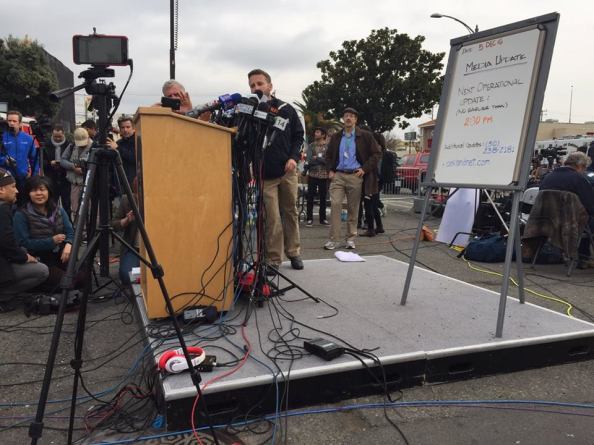

This same lack of interest in the community was reflected in the way the city of Oakland handled its official disaster and clean-up operations in the aftermath of the fire. For over a week after the fire, the city kept the section of International Boulevard around the wreck of the Ghostship closed off. In the first few days, as damage assessment and recovery operations occurred, this was an arguably reasonable decision, especially in view of how critical it was to provide information for the families involved. But after there was any legitimate excuse, city officials kept this portion of the street at the intersection of Fruitvale Avenue and International Boulevard—a main artery for the busy neighborhood—closed because they had transformed it into their public relations stage.

City, police and fire administrators gave updates and press conferences from the small stage they had constructed so that the Ghostship ruin would be visible in the background as they gave updates and speeches to the growing body of local and national media reporters. The rest of the blockaded area was reserved for mobile satellite link trailers, news van and reporter parking. The official media pen became a fixture of the blockade for its duration of ten days, blocking off access to residences and businesses alike, as well as the local low-income clinic, Native American Health Center, which had to temporarily relocate some of its operations for the entire period to another one of its buildings outside of the media scrum further down International.

The city’s media stage in the penned off area of International Boulevard.

Media vehicles and satellite trucks parked in the penned off area around International Boulevard, mostly used as a parking lot and media stage for the fire spectacle.

Certainly, none of these things may have carried more import than the unfolding details of the awful disaster that engulfed the off-the-books venue and residence at Ghost Ship at the time. But the early establishment of an almost contemptuous universal disinterest in the the neighborhood residents became the template for the subsequent politicization of the disaster, and it was not one that was easily changed in the months that followed.

Some good local reporting focused on the hobbling of normative city services in order to continue inflating its public safety budgetary partner, the Oakland Police Department. Subsequent records and whistle blowing revealed a Potemkin fire department facing a myriad of serious failures—absent and powerless chiefs and officials, flagrant bypassing of protocols, and questionable budgetary expenses. The OFD failed at its minimal fire prevention due diligence–even in the wealthy Oakland Hills area, a fact made even more alarming by the city’s hesitance and near-illegal attempts to keep the records from going public. But an overwhelming lurid focus on the personal life of Derrick Almena—the master tenant and designated villain of the media narrative—made such reporting difficult to find, especially in national papers of record.

Where substantive reporting on the politics of public safety was rare, there was almost no reporting at all about the brick and mortar community in which the disaster occurred. It was as if the Ghostship had existed on a floating island, connected to the affluent communities laying emotional and thematic claim to it by magical escalators placed around the city everywhere but Fruitvale and San Antonio. While the conspicuous absence of Black and Brown voices from the neighborhood should have been a red flag of the ongoing displacement of Oakland’s historic communities and their eclipse from the Oakland narrative, no such thing occurred. Rather, discussions about gentrification and displacement appeared frequently in reporting about the fire and its impact, and in the city’s rhetoric and response, but they were focused on fears of displacement of the self-proclaimed “warehouse and live-work” community, not the physical community where the fire occurred. [This offensive Guardian piece is probably the best synthesis of the distillation of gentrification as an issue primarily of artists, the most vital Oakland demographic].

Somewhere along the way, gentrification and displacement had become boutique processes confined to the Oakland community of artists, not the communities where these groups’ lifestyle and habitus often jump-started processes that displaced historical low-income and of-color communities. Affluent new-comers had become the famous Black city’s heart and soul, and the favored protagonists in it’s housing crisis. The indifference toward overwhelmingly Black and Brown population that live in the neighborhood around Ghostship, and the hyper-focus on live-work and warehouse spaces would come to influence policy focus and choices about housing and housing safety in city agencies and government and would echo throughout the mainstream media discourse about the fire for months to come.

II. The Live-Work Heart and Soul of New Oakland

The replacement of Oakland from a historic Black and Brown mecca to a new construct as DIY and artist epicenter began over a decade ago as a spillover effect from San Francisco’s rampaging rents and increasing affluence. It was a logical process. Artists who had colonized San Francisco’s warehouses and industrial buildings naturally fled to Oakland with its then-cheap rents and absent building-code enforcement. The spaces proliferated and Oakland soon gained a reputation for being an off-grid city full of the kind of urban playgrounds attracting young affluent demographics to places like Brooklyn and Portland.

Oakland’s rebranding of itself as a reserve-San Francisco, the new Brooklyn, and the Burning Man headquarters with cheaper and more plentiful live-work spaces was in large part responsible for the accelerated gentrification of Oakland’s downtown—rechristened Uptown–and the subsequently enfranchised sideshow known as Oakland First Fridays. The city officially used the latter for marketing and relied on it as a major draw for tourism and development dollars.

None of this was lost on Mayor Libby Schaaf, who, as a city council person was vocal proponent of the warehouse/arts scene. Her partnership with the founder of high-profile, live-work giant American Steel to create “the Uptown Art Park” highlights how Oakland’s political class came together with a nascent community of well-heeled makers to create a new concept of public art and space and the rebranding of at-risk, and gentrifying spaces as civic goods.

The site of the Uptown Art Park was an empty lot in the heart of downtown Oakland’s former commercial district, miles from Schaaf’s ostensible area of work, affluent district 4. Nevertheless, Schaaf helped the founder of American Steel, Karen Cusolito, propose the “art park” to the city council, and gather facilitation and funding for it. This was no forgotten corner of Oakland, as it was often characterized by Schaaf and Cusolito, however—the block or so surrounding the lot was steeped in Oakland’s gentrification history. The Westerner, an SRO in Oakland’s dwindling cache of housing of last resort, was sold and demolished and the Uptown apartments that surround the lot constructed there a decade earlier.

In 2012, community activists with the help of Occupy Oakland had staged a political action at the lot, taking it over as the new site for the defunct Occupy encampment and using it discursively to highlight the displacement of the area’s previous historic Black communities and the related mounting problem of homelessness. The action was short-lived, with OPD raiding and ejecting the camp the next morning.

Cusolito and Schaaf’s new plans for the lot erased the political and social history of the area. Affluent entrepreneurial newcomers like Cusolito became—in Schaaf’s own words—the legitimate “activists” and the pubic-private art partnership as a “magical example of citizen advocacy”. Gone was the critique of ongoing gentrification in the creation of “Uptown”; rather the real problem as proposed by Steven Huss, an Oakland city government cheerleader for Oakland’s DIY-based arts district and Cusolito, was a space unused for the benefits of the arts community. This was a new equation, with well-heeled artists as Oakland’s legitimate resident, the city’s flagging industrial base as their manifest destiny, and emerging politicos interested in development as their natural patrons. That’s exactly how the National Endowment for the Arts, a funder of the “art park” described Oakland and the “community” that demanded and secured the art park:

Oakland saw a surge of new artist residents when the dot-com boom brought skyrocketing housing costs to the region. Today the city boasts of having one of the highest populations of artists per capita in the nation. Already home to many artistic and industrial fabricators, Oakland became home to a burgeoning community of industrial artists, and today a high percentage of the large-scale interactive artworks shown at the annual Burning Man festival in the Nevada desert are fabricated in Oakland.

Schaaf’s subsequent mayoral campaign advertised a full week of inaugural festivities with “Made in Oakland” as its theme, she held her inaugural party at American Steel, which her campaign called “a playground for artists and innovators” and a celebration of the “artistry and maker-spirit of Oakland”. Later, she convened the Artist Housing and Workspace Taskforce in 2015, with a mandate to explore methods of keeping Oakland affordable for artists including the city’s purchase of housing in land trust specifically for self-identified makers.

Oakland’s reinvention as a city of artistic newcomers gilded the the disappearance of 33,000 African-Americans from Oakland’s geographic and cultural landscape—nearly 25% of its historic population. The city’s long-standing reputation as a Black political and ultural mecca began to fade. As Assata Olugbala, a retired educator, and frequent commenter at Oakland city council meetings noted at a public forum on the Ghostship fire in January, Black people, the true “heart and soul” of Oakland were being erased, over-written by newly arrived artists and artisans eager to adopt and claim Oakland as their own construct. And city government and agencies were clearly encouraging and servicing them.

As a conspicuous example, Olugbala lamented, city governments had failed for 14 years to hold the Oakland police accountable to their federal consent decree and fight police violence against Black communities—but this regularly generated little concern in city hall. In just one short month, as she noted, the city council had rushed to address all the concerns of the live-work and artist groups. Oakland’s artists had not only become the favored child of the establishment but the new cultural face of Oakland, with all the privileges that status suggested.

III. Sanctioned and Unsanctioned Speakeasies:

Thus, its not much of a surprise that artist venues and spaces avoided official OFD scrutiny and OPD policing. In its four years of operation, the Ghostship venue was no exception, and perhaps even an extreme case of official indifference to normatively illegal activity. Police reports that emerged after the Ghost Ship fire revealed that the off the books nightclub operated with the full knowledge of the OPD and city alike. One report describes an OPD officer who responded to neighbor’s complaints of noise being turned away by the doorman and simply leaving. Other reports by OPD describe a “24 hour” art gallery, a rave club and artist warehouse. OPD knew that the space was being used illegally in a myriad of ways and did nothing.

OPD’s laizze faire attitude toward the Ghostship stands in sharp relief to its rubric for other residents in Fruitvale and San Antonio who try to run their own unpermitted culture and entertainment businesses in disused converted warehouses and storefronts in this part of Oakland. Several weeks after the Ghostship fire, the Alameda County Sheriff sent an armed SWAT team to arrest and evict group living and working in a storefront a mile or so from the Ghostship fire. According to the Alameda County Sheriff, the group was running an off the books party venue in East Oakland where gambling and drug use were allegedly occurring.

The ALCO Sheriff claimed to raid the space as a safety precaution inspired by the Ghost Ship tragedy. But its clear that quick violent, carceral action has been the boilerplate response by law enforcement for Oakland’s “other” live-work spaces for years. The criminialization of off-grid venues run by Black and Brown Oakland residents is a regular part of life in East Oakland. In 2015, for example, several blocks from the Ghost Ship in the “Dubs” area of International Boulevard, an underground storefront speakeasy was shut down shortly after it began operating—the police claimed that gambling and drug-use and drinking were occurring at the site, unlawful conduct by Black and Brown historical residents that the city could not market to affluent newcomers. Another illegal gambling spot—described by law enforcement as a casino–was shut down not far from Fruitvale BART on a similar pretext around the same time, scant months after it began operating.

The concerns that prompted the raids aren’t to be found in the criminal code or public safety rubrics, despite the claims of OPD and local authorities. Public police records released after the fire show that OPD were regularly called to the Ghostship with complaints of firearm threats, assaults and thefts and open illegal drug sales. The calls came from within the Ghostship collective from neighbors and neighboring businesses. In terms of the potential for violence, even lethal violence, and harm to the surrounding community, Ghostship posed no less an ostensible threat than unsanctioned venues run by and for Black and Brown community residents. In hindsight, of course, the larger attendance and structural requirements of activities in Ghostship, made it a much graver threat to public safety as the city came to unfortunately discover. The real difference in official response was not one of public safety–its that the other venues mentioned here were operated and frequented by people of color from the neighborhood.

IV. Misunderstood Lessons and Unheeded Warnings.

Not surprisingly, despite dozens of anecdotal tales of artists suddenly being evicted from their spaces by city planning or the Oakland Fire Department, nothing of the sort happened. The die was already cast, however. The narrative of a community of embattled warehouse residents facing stringent and unfair enforcement of code became the dominant legacy of the Ghost Ship fire, politicizing the tragedy and the mourning that followed in ways that in hindsight make little sense.

The Ghost Ship was an atypical live-work space, crammed from top to bottom with extremely unsafe fixtures and decorations. It was a functional nightclub with well-publicized shows that drew tourists and others from all around the Bay Area. As many observed, given its regular use as a public venue for profit, its lack of exits, the large amount of flammable material, and bad management, Ghost Ship was a tragedy waiting to happen. The live-work space was uniquely dangerous in the context of Oakland’s off the books venue scene.

The popular narrative grew a life of its own, however, and bypassed more obvious takeaways from the fire. Three significant tropes became the immutable template for the city’s response, media reporting, and statements by self-proclaimed artists and live-work residents themselves. The first, and perhaps most key, was the definition of the community affected by the fire. This community was rarely defined in geographic terms, i.e., the adjacent brick and mortar businesses, and dwellings and people who lived and worked in them—working class people of color with long-standing cultural roots in the community. Rather, the community affected by the Ghost Ship fire was ethereal and amorphous, typically populated by white newcomers to Oakland—many from affluent or middle class backgrounds.

The voices of this community gained further privilege through the moral gravity and national spectacle of the Ghostship fire and they were given carte blanc on the stages of government to craft the second and third tropes. Usurping the role of Oakland’s displaced, they insisted that this community had been forced by the urgencies of the housing market to live in dangerous warehouses. In turn, for this reason, the live-work community needed focused institutional support to rehabilitate their last-resort living situations. Then they claimed that instead of such support, city agencies were preparing to aid in their eviction and displacement.

These twin beliefs spawned several fundraisers and benefits to increase safety in existing live-work spaces, and to bring sites up to code for the predicted storm of enforcement. Over a million dollars were officially raised by independent crowd-sourcing for the victims of the fire. But additional funds were raised for people had nothing at all to do with the fire, but lived in supposedly similar conditions to fund DIY repairs and upgrades of existing rented live-work spaces.

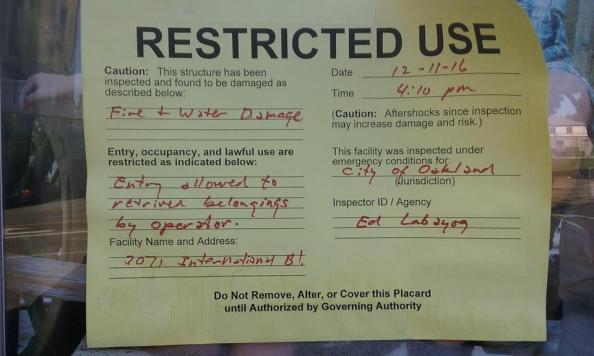

The welfare of the surrounding community that the Ghostship fire occurred in never entered into the discourse—not about housing of last-resort, not about fire-safety, and certainly not as the subject for fund-raising. The businesses in the adjacent building to the Ghost Ship venue were immediately closed in the aftermath of the fire, and within a week were yellow-tagged—basically shut down for business. One owner who I spoke to, who wanted to remain anonymous, told me that no one had ever approached her about fundraising for their shuttered businesses, and that they had, to date, received no funds from any source.

Yellow Tags on businesses in building adjacent to Ghost Ship mean that the site can’t do business indefinitely.

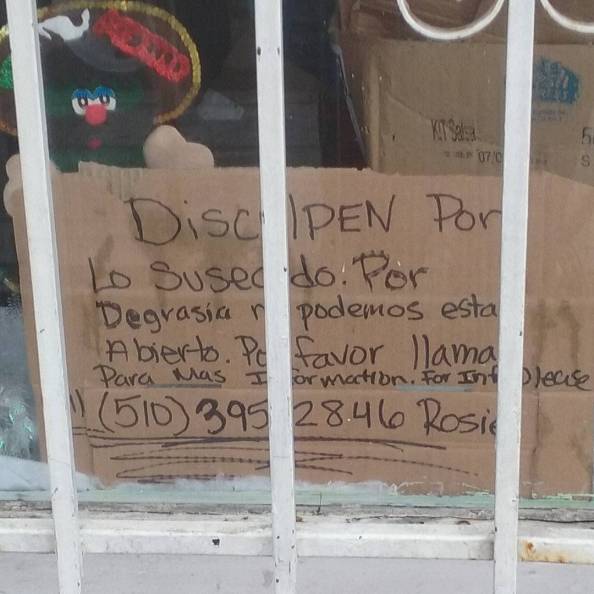

Sign on a business around the corner from Ghostship that was damaged in the fire: “Pardon us for the events, Unfortunately we are not able to open. Please call for more information:”

La Moda photographed in March, 2017, liquidating its inventory in sidewalk sales because it can’t do business in a yellow tagged store.

As I looked at the collapsing, water-damaged ceiling and the water-damaged furniture and display cases, they told me the city had offered them a loan, which they would have little hope of paying back given the damage their livelihood. The last surviving business adjacent to the Ghostship, La Moda, a woman’s clothing and fashion with its Spanish-language signs and ads, was forced to liquidate its inventory via sidewalk sales in front of the shuttered business in April. But there were no human interest stories about the loss of these businesses, and, to this day, no fundraisers.

Nevertheless, the mythology about a besieged community of artists consequently generated a political movement. A consortium of live-work residents created several “artist” coalitions in the subsequent weeks, that followed the fire. The most prominent, the Oakland Warehouse Coalition, garnered an extraordinary amount of influence and attention immediately from City Council officials and the mayor herself.

Within three weeks, the group had convinced city council member Rebecca Kaplan to give them an official audience in the city council chambers. Though Kaplan invited other affordable housing advocates—including more than one that suggested the city focus on rehabilitating distressed housing for the homeless and precariously housed—OWC dominated the proceedings and had the only policy proposal that was given serious attention as potential legislation.

The immediate and focused response was an extraordinary action by a Mayor and city council to ameliorate such a small and relatively new group. In public meetings, members of the OWC often seemed to be working as partners with Rebecca Kaplan’s aides to consolidate items on the docket for future consideration by the city council. They were treated as stakeholders, literally as a city agency of their own, with the director of the OWC addressing the committee without a speaker’s card. As a testament to the importance of seeming to focus on the welfare of this constituency, Mayor Schaaf issued an executive order around live-work fire codes within one month of the fire.

V. Lost Opportunities

Some argued that the focus, any focus, on housing in the current wildfire of displacement and sky-rocketing rents in Oakland was beneficial. And its true that the fire gave councilperson Kaplan an opportunity to revive a revamped red-tag relocation ordinance that had sat idly in the community and economic development committee for over a year. But the quality and substance of the city’s responses were affected by its never-ending focus on the self-identified artist community in a way that warped Oakland’s long-standing issues around poverty, racism, displacement and increasing gentrification.

Warehouses and industrial sites made into live-work spaces by newly arrived artists are, in Oakland’s vast terrain of off-the-books residences, a tiny minority. The disinterest in existing of-color, struggling Oakland communities erased the reality that they live in hotwired and unofficial domiciles—garages, inlaw units, sheds, basements and unpermitted additions. Such units are not a lifestyle companion to a cultural milieu. In many cases, last-resort dwellings of this type may be the only way working class and poor people have remained in their Oakland communities, where official units require capital, contracts and established credit.

Even normative housing legislation isn’t enough to ameliorate these living situations. Shifting from one dangerous unpermitted unit to another, with, for example, Kaplan’s increased red-tag relocation legislation, is not a guarantee—Oakland’s poor and poorly housed hold on to bad living situations of their own accord because there are few options available even with the funds to do so.

And, of course, fire safety is by no means the only concern in such sub-standard housing. Fruitvale’s epidemic proportion of building-sourced lead contamination—with up to 7% of children exposed—made national news for a day or two around the same time, but with the exception of some busy work by city council members, was soon forgotten in the rush to tend to the Ghostship aftermath. The focus on policing of building safety remained on tenants; lacking established and regular city action to force landlords into compliance, a disproportionate responsibility is on those who have the most to lose.

The city did little to focus the post-Ghostship energy into substantive changes to the city’s degraded code inspection regimes and the toxic sub-standard housing Oakland’s dwindling Black and Brown population were increasingly forced to live in—a reality that would soon become horrifyingly apparent.

VI. Predictable Outcomes

Oakland government’s rush to flatter a small influential demographic had predictable outcomes, and they became clear in a serious fire a few months later in gentrifying West Oakland which destroyed an SRO-like transitional housing building. Four residents were killed in early morning hours in the apartments located in a gentrifying West Oakland neighborhood on San Pablo Avenue, and at least 80 were displaced.

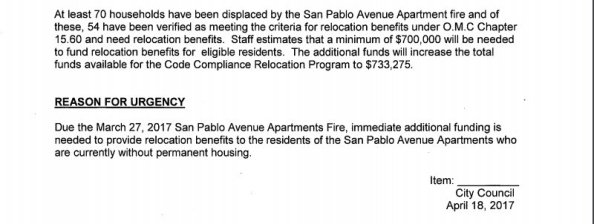

The city’s newly revamped relocation legislation was probably the only sober and useful tool for such a fire, as it improved on existing legislation that provided funds for displaced tenants to later recoup the funds via liens placed on the properties of the landlord. But the necessity of performing its quick passage as engagement with live-work residents masked the fact that the city hadn’t allocated the funds to cover so many precariously housed renters in a city as large as Oakland. What should have been a clarion call to prepare for the relocation of dozens, if not hundreds of poor and working class tenants in the event of another fire of equal magnitude in a large apartment building, went unheeded.

Weeks after the San Pablo fire, it was revealed that the city had still not charged the relocation fund, while victims of the fire waited without answers, and some had become homeless. Relocation funds had not been a pressing issue for the few displaced tenants of the Ghostship months earlier; they had personal resources on top of tens of thousands of dollars from various fundraisers. There was no need to perform due diligence for that audience about where the money for the fund would come from in the future, and so no move was made to make sure the money would be ready in the case of another disaster(s) involving more resident survivors with fewer resources. The passage of the ordinance at the time was seen as a hard-won concession by the live-work community, and a victory of the OWC campaign.

It was later revealed that the relocation fund only had about $150,000 at the time of the San Pablo fire, months after it had been retooled.

Eventually, council-members performed a byzantine transfer of funds in a council session in mid-April, taking $600,000 from an unrelated housing program to fill the fund for displaced San Pablo Avenue residents. Though the city had waited an astonishing three weeks before taking action, it now has no ready source of funding for relocation for a future emergency of similar magnitude—after these relocation payouts the fund will drop to zero. There are more problems. Relocation amounts are calculated by units, not necessarily by the number of people living in them—another weakness caused by an inaccurate assessment of the conditions experienced by residents of sub-standard units. This may create future problems for adequately addressing displacement of these and future precariously housed residents.

A single-minded focus on protecting the residency rights of self-identified artists was a reversal of the logic that prompted building fire codes and fire inspections—as ways of protecting socially vulnerable poor and poor people of color forced to live in sub-standard housing. That focus also blurred the code enforcement department’s struggle with competency and efficacy through the years. As the East Bay Express reported months later, policy for a city apparatus that would create pro-active building code enforcement coupled with rigorous renter protections to keep people in their homes or in parallel housing had been recommended in numerous housing reports provided to the city. But even when a proposal to create a taskforce to hammer out a system that would preserve residency and hold landlords accountable entered into the city council’s agenda last year, it was frozen in committee.

Though the Ghostship fire would have been an opportunity for reviving the proactive policy proposal with added support, staff and funding, it was never even discussed—in forums, in city council meeting after meeting, no councilperson brought it up, nor did the warehouse advocates. Rather, the focus remained on sculpting a code enforcement profile that would maintain the right of newly arrived residents to live in exactly the kind of social and structural mis en scene they desired—a right that they seemed to claim in statement after statement was derived from their single-handed role in creating Oakland’s culture. This deviated the conversation away from stronger code enforcement and protections for the historic residents in the kind of domiciles they live in. Issues of poverty and racism rarely entered into the conversation, which was invariably about the right of enterprising live-work artists to invest significant funds into tweaking their own undocumented residences.

The bill for passing on those policy opportunities had come due much earlier than anyone may have anticipated in the form of the San Pablo Avenue fire. In contrast to the city’s kinetic response to the Ghostship disaster, initial response to the San Pablo fire was ponderous. For most of the following day, Mayor Schaaf occupied the public stage in tit for tats over the fruitless Oakland Raiders negotiations and didn’t mention the fire publicly. There was no on-site stage for round the clock press conferences, and there was no vast migration of the nation’s news media. The surviving residents, numbering more than 80, were crammed into a youth center, where they spent over a week sleeping on cots, because there are so few low-income housing and SRO buildings left in Oakland to relocate them to in Oakland’s gentrified landscape. Despite the obvious implications of Ghostship, Oakland had no designated emergency shelter put in place and still doesn’t.

Subsequent records releases show that Oakland Fire officials called for closure of the building as an imminent risk to the lives of the residents months, and then even days, before the fire. But, as is typical when tenants are poor, and especially in the post-Ghostship discourse on fire safety that privileged affluent live-work residents as their own handymen, nothing was done. Not surprisingly, it was also revealed that the owner of the building, Keith Kim, had cozy relationships with the city, both in the past and present. In an unbelievable coincidence, one of Kim’s occult business ventures was voted up by the city council the very next night.

It also became evident that the non profit running the transitional housing in Kim’s building had a checkered past and odd practices. In the vacuum of adequate low-income housing, actors with questionable intentions had appeared to either exploit the crisis or fail miserably at providing safe housing due to their lack of capacity.

The San Pablo fire became a public stage where Oakland’s age-old institutional priorities guided by institutional racism and the inescapable logic of gentrification played out. The city’s corrupt and incompetent code enforcement failed Oakland’s most vulnerable. The San Pablo building’s residents were nearly 100% African American, the same demographic that had experienced an almost complete loss of available low-income housing and forced exodus during Oakland’s live-work renaissance. The city’s ho hum response to crisis involving the city’s Black heart and soul—the very reason OPD was still in federal stewardship after 14 years, as Olugbala noted—was in full view.

Oakland’s artists, who are mostly white, fared well by contrast. The alarming scenario that pro-warehouse proponents painted, never came to be. Local media reported that there were only 4 red-tagged buildings city wide in the months following the Ghostship fire, somewhat less than the same period a year earlier. Two of those were storm-damaged houses in the hills. Only one ostensible live-work building was red-tagged, but that was because a fire gutted it a few weeks after the Ghostship disaster. In fact, the city red-tagged only one-building for non-disaster related habitability or fire code violations–the storefront mentioned earlier raided by the police and used by mostly Black and Brown Oaklanders.

In an impoverished conversation about fire-safety and livability, the city and warehouse advocates patted themselves on the back. They had created the problem and the solution, and it didn’t matter that they’d failed to address the daunting issues of sub-standard housing and renters protections that the moment called for.

Weeks later, the San Pablo fire has engendered no public forums, no raucous city council meetings–a handful of speakers appeared to speak at the city council vote on the increase in relocation funds on April 18, 2017, and most were victims of the fire or their family and friends. The one-hundred or so African-American fire survivors have moved to various other sites, according to local reports, dispersed through the city in precarious, often temporary housing. Some are homeless; some who had mental health needs, are lost to the streets. Mayor Schaaf has stated that she will hire more inspectors, but no council person has taken it upon themselves to introduce legislation to protect residents nor to guarantee that there is a rigorous increase in inspections. Having swept San Pablo under the carpet with additional 600k infusion to the relocation fund, the city says done and done.

Meanwhile, La Moda, the last surviving business adjacent to the wreck of the Ghostship puts on sidewalk sales by the sound of a gas generator as the owners try to liquidate their stock before letting go of their business. The Botanica, which had been there for years, and was a material part of the religious culture of the area, irreplaceable, is gone without forwarding address. The site of the fire has become a tourist attraction, conveniently located close to BART, with small crowds regularly taking selfies of their pilgrimage.

No one knows what will become of the nearly block-long series of structures, though they will probably be converted to market rate housing as soon as its feasible to do so. As of this date, victims of the San Pablo fire have still not received their relocation funds, although the city administrator claims the checks will be cut by the end of April. Fruitvale’s decades-old toxic lead contamination continues. The city council failed to introduce legislation to address Fruitvale’s lead problem when the issue made national headlines, and proposed policies seem to have died in committee. It makes no difference to Oakland’s new heart and soul, which have moved on regardless.

Posted on April 20, 2017

0